Understanding the relationship between speed and torque is essential for selecting and effectively using stepper motors. This guide explains the key concepts and how to interpret performance curves for your applications.

What is Torque in a Stepper Motor?Torque is the rotational force that causes the motor shaft to turn, quantified in Newton-Meters (N·m) or milliNewton-Meters (mN·m). In practical terms, torque represents the motor’s ability to overcome mechanical resistance—such as friction, inertia, or external loads—and initiate or maintain motion. Although torque is just one of several key motor specifications, it is fundamental in assessing whether a motor can meet the mechanical requirements of an application, ensuring reliable operation under expected load conditions.

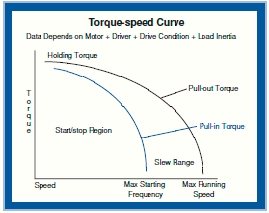

How to Read Torque/Speed Curves

A torque/speed curve visually defines a motor's operational limits. Crucially, this curve depends on both the motor and its driver – the same motor can perform very differently with different drivers or supply voltages.

Key Regions & Terms on the Curve:- Holding Torque: Maximum torque when powered but stationary (windings energized).

- Detent Torque: Passive torque from the magnetic detent effect when the motor is unpowered.

- Pull-in Curve: Defines the maximum torque for starting, stopping, or reversing instantly at a given speed. Operation beyond this curve requires acceleration ramps.

- Pull-out Curve: Shows the maximum torque the motor can maintain while running smoothly. Exceeding this causes stalling.

- Slew Range: The area between pull-in and pull-out curves where the motor must ramp speed gradually to stay synchronized.

Torque is directly proportional to the current through the windings and the number of coil turns. Increasing current by 20% increases torque by roughly 20%, but exceeding twice the rated current risks damage and offers diminishing returns due to magnetic saturation.

The main enemy of high-speed torque is winding inductance. Inductance slows the rate of current change, defined by the electrical time constant: τ = L / R (inductance divided by resistance). At high step rates, current cannot build up fully before the driver switches to the next phase, reducing effective torque.

- Increase Driver Voltage: A higher voltage forces current into the windings faster, counteracting inductance.

- Use Bipolar Parallel Wiring: For 8-lead motors, this configuration lowers inductance compared to series wiring.

- Select Low-Inductance Motors: Designed specifically for faster current rise times.

- Implement Microstepping: Modern drivers with advanced microstepping can smooth motion and sometimes improve mid-range torque.

Rule of Thumb: Your application's required torque should stay within the pull-out curve with a 20-30% safety margin. The start/stop region must cover any required instantaneous moves.

For high-speed applications, prioritize motors with lower inductance and pair them with higher voltage drivers. For low-speed, high-torque applications, focus on motors with higher holding torque and use bipolar series connections.

ConclusionMastering the torque/speed relationship means looking beyond static torque ratings. By understanding how driver voltage, winding inductance, and current interact, you can select the optimal motor-driver combination and configure it to deliver stable performance across your required speed range.